Quake's Bizarre, Beautiful History: Episode One

How Quake Changed Everything - and Itself - Constantly

Happy birthday to one of my favorite games ever, Quake! On this day 29 years ago, id software changed the gaming landscape once again with their latest, greatest shooter. As the godfather of competitive online multiplayer with a unique, atmospheric single-player campaign, it paved the way for countless games which would follow. Despite this, you don’t hear about Quake much anymore, even as its older siblings Wolfenstein and Doom see modern success in a gaming landscape of fans returning to the “boomer shooter” formula. For all that Quake has accomplished, though, it has always struggled to nail down an identity for itself, both shaping and being shaped by the industry around it. Why was Quake great, and why did it fall by the wayside? You’ll find the answers to all this and more in this series of articles. It’s a deep-dive into the history surrounding these games and how players experienced - and continue to experience - them today.

As always, there’s no better place to start than the beginning. The story of Quake begins six years before it first hit shelves, when it was little more than a beguiling dream…

Whispers From the Past

This is a promotional screen from Commander Keen in Invasion of the Vorticons. Released in 1990, this was the first game from the four-man team which would become id software. John Carmack invented the smooth screen-scrolling technology which worked even on standard IBM-compatible computers. John Romero inspired the basic premise and helped Carmack program the game. Tom Hall shaped the game’s general design. Adrian Carmack (no relation - seriously) brought the game’s visuals to life. This was the beginning of one of the greatest streaks of innovation of any independent game studio. What you see before you was their next plan: The Fight For Justice, starring none other than John Romero’s favorite Dungeons and Dragons character, Quake. The most interesting thing about reading this little promo today is that it sounds absolutely nothing like Quake.

Quake would never forget Commander Keen, though:

The Fight For Justice is a shockingly ambitious proposal for 1990. Fully-animated backgrounds, a promise of detailed lives and personalities for every NPC, and decision-making structures that vastly affect and are affected by the world at large? They probably could have figured those fully-animated backgrounds out, but games wouldn’t really solve such complex world design for another decade at least. Even the folks at id realized this soon enough, and they decided to put a pin in The Fight For Justice in 1991 so that technology could catch up to their grand vision. In the meantime, they helped push technology along with Wolfenstein 3D and Doom, creating the first-person shooter genre in the process and inspiring countless imitators.

Anyone with a creative mind has had the sort of project in their head that I imagine Quake was for John Romero. It’s something big, perfect, and personal that always lives somewhere in your head. Even if you can’t - or haven’t - actualized it in any meaningful way, somewhere in there you know exactly what it’s supposed to look like. You know that, if you could just make it real, everyone would love it just as much as you do. Luckily for Romero, he had a team he knew he could trust to realize Quake, and they were a team well accustomed to breaking new ground. If John Romero had his way, Quake was going to be a brand-new fantasy game unlike anything id had done before, but dream projects like this one rarely come out looking the way they did in your head…

Dimension of the Doomed

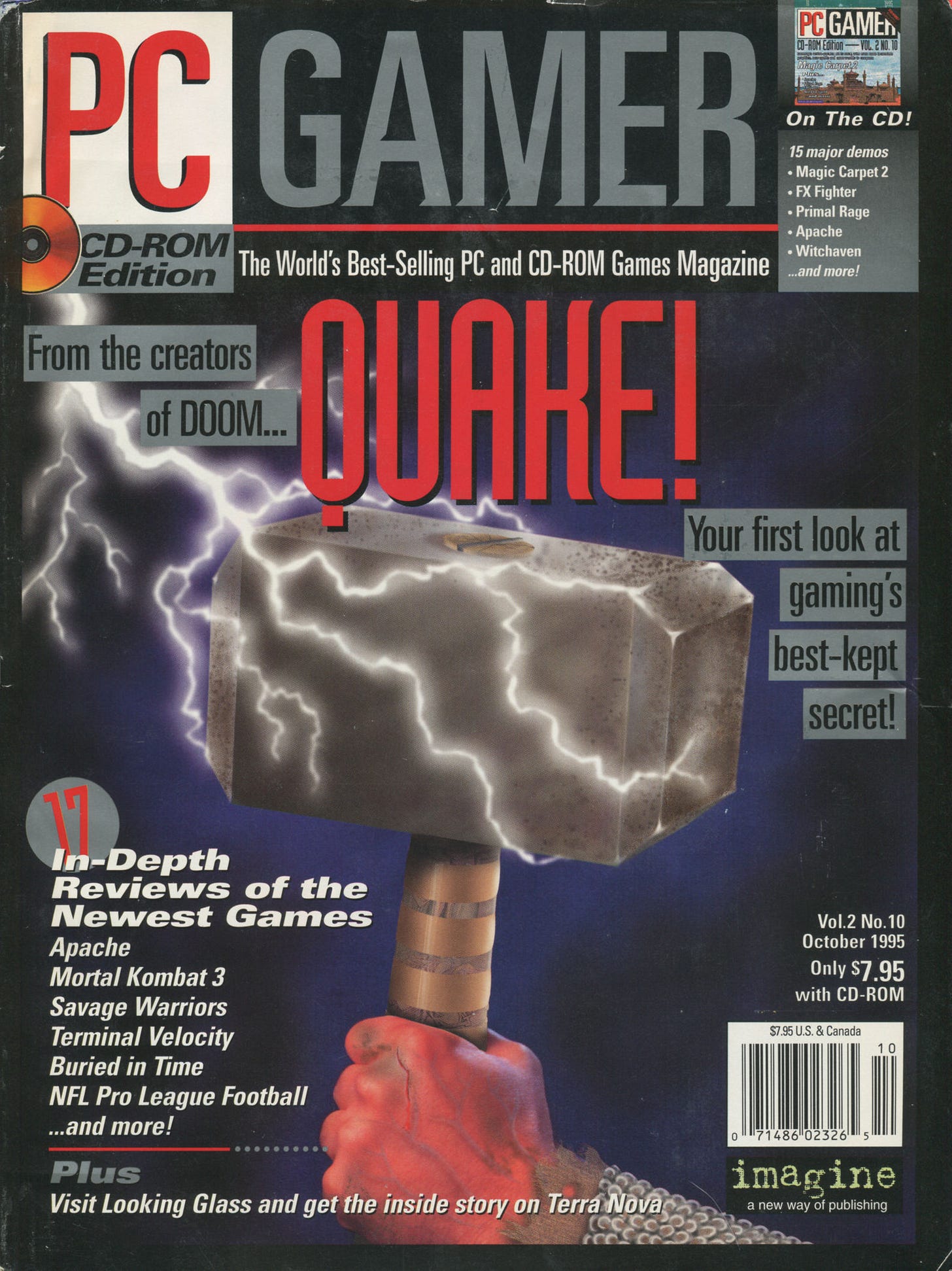

After 1994’s Doom II, id finally felt like the world was ready for Quake and began work on a fully-3D graphics engine. Aspects like the fantasy setting and the hammer-toting hero remained intact from the original concept, but by now, Romero had shifted the focus more in line with id’s reputation for action games. This surely surprised no one. After all, John Carmack is the one who famously compared story in video games to story in porn: “It's expected to be there, but it's not that important.” He has since amended this statement in the face of mountains of evidence to the contrary, but I digress. Basically, “It’s medieval” and “It’s an action game” was about the long and short of what id was willing to say about Quake for most of its development, and we see a window into that vision of the game in PC Gamer’s October 1995 issue.

Writer Steve Poole paints a picture of id with their noses deep in their work on Quake. With Romero out of town and John Carmack leaving him waiting for hours, he ends up having a lot to say about the game’s specs and its immersive environments, but little more than a few concepts to relay about the gameplay. He’s told that your character will be a realistic, fully modeled entity that can get bounced around the walls by hard hitting enemies, leaving blood smears in his wake. Mentions are made of online networking features and competitive multiplayer, but there’s no indication of what form these things will take. id’s Jay Wilbur also let it slip that Nine Inch Nails - all fans of Doom, apparently - were working on an experimental soundtrack for Quake - more on that later. Pictures from Poole’s early experience with Quake look surprisingly recognizable, but with naught but a superimposed dragon to populate the maps and vague hints at gameplay, it’s kind of surprising how excited he sounds. id says they hope Quake will be ready by Christmas, but something is not right.

The truth is, Quake’s development was a mess. Ever a programming prodigy, John Carmack was developing a groundbreaking 3D engine and a new networking model for the game at the same time, which ended up being more than even he could comfortably handle. Map-makers like Romero and Doom vets American McGee and Sandy Petersen were constantly redoing their work for it to function properly on the ever-changing engine. By the time the engine was finally finished, a lot of work had ended up on the cutting room floor and progress on the actual gameplay - always priority number one for id - was nonexistent. The burned-out developers wanted to get this thing over with as quickly and easily as possible, and there was no better way to do that than to do what id software did best - make a first-person shooter.

Unsurprisingly, Romero wasn’t on board. “We don’t want to do Doom III,” reads a quote from John Carmack in Poole’s PC Gamer story. Quake had been whispering beyond the veil to Romero for over six years, and it had been something original and ambitious for as long as he’d been dreaming about it. Yet here he was, watching it turn into something that looked a lot like Doom III. Gone was the living, breathing world where NPCs had lives and your choices really mattered. Quake couldn’t even hold onto the barbarian it was named after. Though he relented to his exhausted team’s whims, Romero’s dissatisfaction would ultimately lead to his departure from id after Quake’s release, making this the last title from the original id lineup.

Once they knew what Quake was, id crunched the rest of the game out in roughly seven grueling months. Those familiar with the history of game development know that such stress tends to be a bad sign, but the creative process is a curious thing. If Quake had been what Romero wanted it to be, we might remember it more like the first few Elder Scrolls games: inferior stepping stones to modern titles which would be made for hardware that could handle massive worlds and stories. However, the decision to drop a shotgun-toting marine into these oppressive dark fantasy worlds ended up making Quake something more than that. id was well-accustomed to changing the gaming landscape by now, but I have to wonder if even they could have predicted just how important this troubled title would end up being…

Witness the bizarre beasts and strange sights of the game that would change gaming forever in “Episode Two: Quake Shakes the World!” Coming soon.