Welcome to Expansion Pack Two of “Quake’s Bizarre, Beautiful History!” Read the previous episodes here:

Between 1996 and 1999, id software was truly on a roll with Quake. Carrying the momentum through from the breakout success of the Doom series, Quake’s three installments in four years pushed technology forward and fostered a lively community with online multiplayer. After Quake III: Arena’s official team-focused expansion, Quake III: Team Arena, released on December 15th, 2000, id was looking to step back from Quake for a spell. After all, a multiplayer game with such a dedicated community could last for a while (even with Unreal Tournament competing with it), and John Carmack wanted to go back and give ol’ Doom some love.

Many at id, a studio which had developed a habit of iterating on their old titles even by accident (*cough* Quake II *cough*), doubted that it was a good idea to go back to the well on Doom. Luckily for Carmack, though, Grey Matter Studios released Return to Castle Wolfenstein - a title id had licensed out to them - to positive reception in November of 2001. With a franchise as dusty as Wolfenstein managing something of a comeback, id got on board with Carmack’s proposed modern Doom remake and set forth with a unified vision. For the time being, Quake was on the backburner, and id was knee-deep in work on their newest iteration of idTech for Doom’s revival. While Quake takes a break, we need to zoom out and take a look at the kinds of shooters everyone else has been making.

The Other Guys

For a long time, id was the company that defined just what a first-person shooter was. In fact, they were called “Doom clones” long before they came to be called shooters (though genre terms were far less defined back then and remain somewhat blurred today). This isn’t just because Doom was the biggest deal; it was because Doom’s fundamental structure was the template these games followed. Even if they didn’t run on Doom’s engine - and many did - they consisted of sprawling mazes filled with enemies that you had to run-and-gun your way through with a wide arsenal. Duke Nukem, Blood, Heretic, and more followed this structure with their own thematic spins or unique features, but the overall feel remained pretty stagnant. Some developers, however, weren’t content to let shooters be so narrowly defined, and they got to work quickly.

In comes Valve with Half-Life in 1998, a big deal of a game based on Quake’s engine which I’ve already brought up a couple times. It told an interesting story with events that unfolded around you in real time without any clunk. At a basic level, it felt very much like Quake and other “Doom clones,” but a more realistic arsenal and a focus on multifaceted problem solving with the physics system brought something new to the table. Counter-Strike, a mod for this game’s multiplayer which Valve would later elevate into a standalone title, doubled down on strategy in a player-versus-player environment. Death lasted until the end of the round, tactical equipment like smoke and flashbang grenades was introduced, and shooting involved realistic mechanics like recoil, reloading, headshots, and accuracy penalties for shooting while moving. In both single-player and multiplayer experiences, players were excited for more grounded, strategic experiences that id’s action-first titles didn’t provide.

Experimentation with more immersive worlds and less bombastic approaches to shooting continued in parallel with Quake’s own growth. One aspect of this was the growing interest in designing shooters that played well on consoles. In their early days, shooters were seen as a PC-centric genre, with the only shooters on console typically being compromised ports of games which debuted on PC. Because console control schemes didn’t accommodate games focused on speed and precision like Quake as well as the mouse and keyboard did, console shooters would come to favor these new design trends. As consoles headed into their fifth generation where 3D visuals were becoming standard, developers and publishers wanted to make shooters a success on both markets. Nintendo subsidiary Rare had the first major success in this field with Goldeneye and Perfect Dark, two shooters that were actually pretty functional in spite of the oddity that is the Nintendo 64 controller.

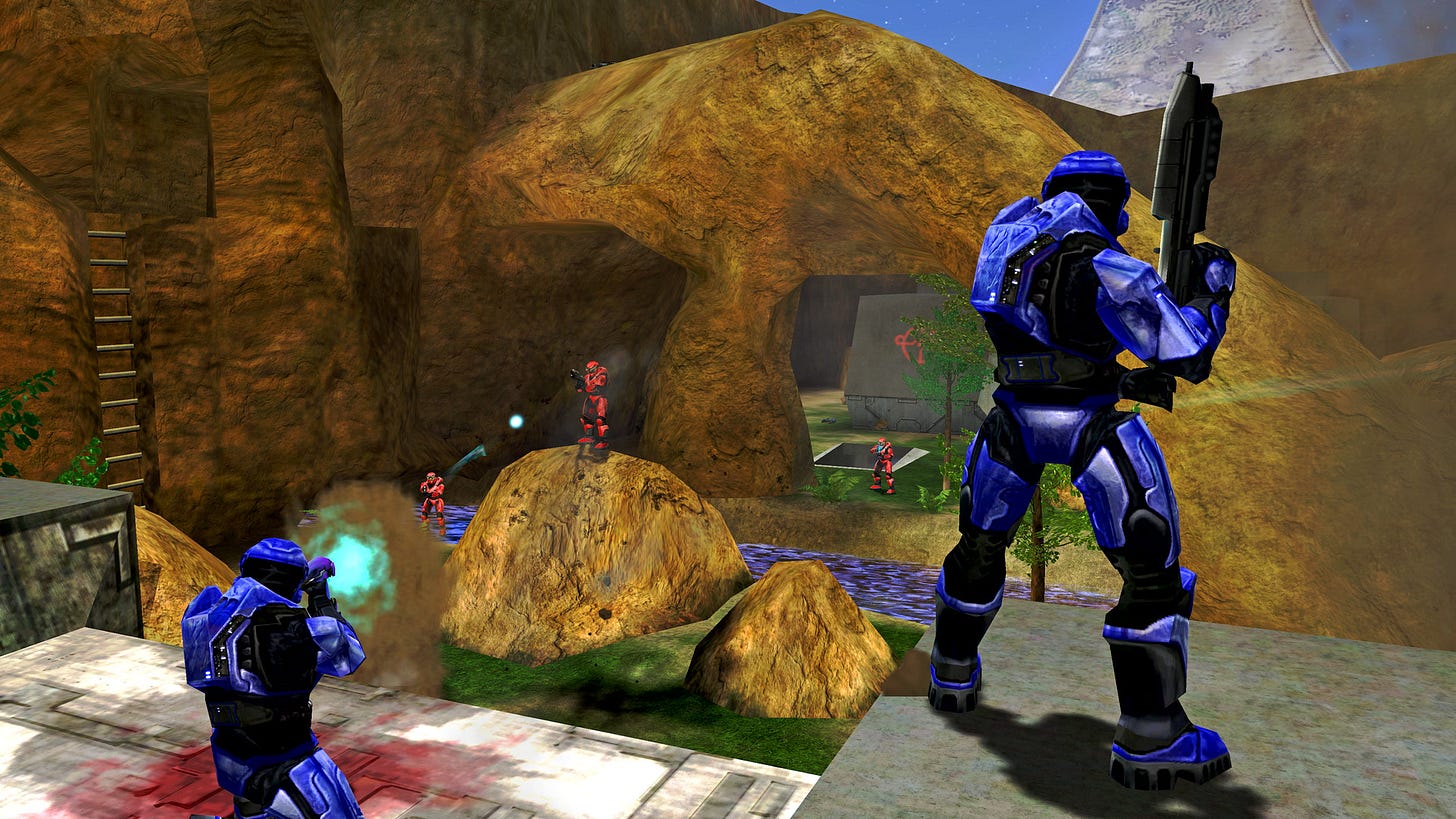

The sixth generation is where shooters really started to feel at home on console. In 2000, Timesplitters on PlayStation 2 would become the new Goldeneye in many ways. 2002 saw the release of Retro Studios’ Metroid Prime, a Gamecube-exclusive shooter adaptation of the Metroid franchise’s hallmark style of exploration which featured a meticulously detailed and interesting world. The culmination of all this experimentation was the franchise which would become the new icon for the genre, Halo. Featuring a cinematic narrative structure, large and interesting environments, and a legendary multiplayer experience with up to 16 players in big battlefields, 2001’s Halo: Combat Evolved was an instant success that single-handedly allowed the Xbox to break onto the console landscape. Though it followed the general structure of the arena shooter, limitations like slightly more realistic gunplay, slower movement, and only being able to hold two of the game’s eight guns at a time blended in some aspects of tactical shooters and made the game feel more approachable for general audiences. Furthermore, Halo: Combat Evolved’s control scheme was so far ahead of every other shooter on console that the whole industry adopted it in no time.

This isn’t to say Quake was out of the picture. Quake III: Arena maintained a strong playerbase for years after its release. Even though Quake was able to coast for a little while, general audiences were starting to favor these more accessible, widely-available titles. id wasn’t blind to this, seeing the value in fleshing out environments and telling bigger stories. Even though id wasn’t dethroned so much as it was sharing the spotlight, they were intent to implement these features in their newer titles to stay as relevant as possible. As id showed fans their efforts in keeping up with the times in Doom 3 on August 3rd, 2004, they could never have anticipated the kind of competition they faced - or how small it would make their attempt seem.

The Year 2004

The hotly-anticipated Doom 3 lands on store shelves on August 3rd, 2004, and fans are feeling pretty mixed on it. Rebooting the series with a similar premise of a demonic invasion on a Mars base, it leveraged idTech 4’s sophisticated lighting to gear the game more towards a horror atmosphere. It’s heavily populated with dark, cramped hallways, monsters have more grotesque and unnerving designs in comparison to the more cartoonish demons of previous Doom games, and the game focuses much more on designing believable environments and side characters. Functioning as a seamless mission through the scientific facilities of the base with new realistic features like using a flashlight and reloading, it becomes immediately obvious that this is just id trying to split the difference between Doom and Half-Life. When a big title really makes an impact in a genre, you’ll often see every competitor falling over themselves to say “Look, we can do that too!” Doom used to be the template, and now it was squeezing itself into the new one.

Critics were happy enough with Doom 3, but fans were not. To Doom fans, it felt like a compromised version of what they loved. You were slower, the shooting didn’t feel as good, and the mobs of aggressive enemies were replaced by a few weird-looking monsters in repetitive, tight corridors. To horror fans, though, it felt too much like Doom. Your wide and powerful arsenal cut down on the tension; at the end of the day, you were still too strong for all the dark hallways in the world to truly frighten you. As is so often the case, trying to appeal to everyone made the game appeal to no one. Some still defend it these days, but it was generally forgotten. That wasn’t just because of its own mediocrity, though. Those among my readership familiar with video game history probably know where I’m going with this already.

November of 2004 dropped some absolutely nuclear sequels onto the shooter scene. First up was Halo 2 on the 9th. Expanding even further on Combat Evolved’s narrative, scope, gunplay, and variety, its campaign was an even better example of one of the single most widely-appealing shooter campaigns ever made. Furthermore, it was now fully equipped with online multiplayer thanks to Xbox Live, absolutely ballooning the popularity of its multiplayer component. Its many base gametypes and customizable rulesets made it a legend, only prevented from trampling Quake III: Arena entirely by the barrier between PC and console audiences.

As if this wasn’t enough to not only embarrass Doom 3 but push Quake’s multiplayer out of vogue, the second payload made landfall on the 16th: Half-Life 2. By God, this game still impresses me and it’s 2025. The world of Combine-occupied Earth feels perfectly fleshed out as you experience it all naturally playing out in front of you. The characters are so believable, and you really come to care about them. All this while the gameplay doesn’t miss a beat compared to Half-Life; the game expands on its physics puzzles with the ability to pick up tons of level props and even use them as creative weapons with the gravity gun. Even as games today tell bigger stories with better acting and visuals, Half-Life 2’s seamless marriage of creative, fluid gameplay and real-time storytelling that didn’t rely on cutscenes has still rarely been matched.

I’m saying all of that now; how do you think it felt in 2004? How do you think it made shit like Doom 3 look? It can’t have been good. If Quake, or even just id in general, were going to survive in a shooter ecosystem with so much experimentation and innovation, it was going to take a serious effort. Was id willing to put in the work?

Can Quake 4 live up to modern standards of storytelling and immersion? Find out in “Episode Five: Follow the Leader,” out now!

Nice piece. But oh man, I loved doom 3, at least when I first played it! Might be time to try it out again