Welcome to Episode Six of “Quake’s Bizarre, Beautiful History!” Read the previous episodes here:

2005 comes and goes, and that’s about the best you can say about Quake 4 with it. Paired with the already-lukewarm response to Doom 3, id is starting to get a reputation for designing fancy technology only to make games that felt dated and uninspired with it. At a crucial nexus for the industry, id had made the wrong calls to keep itself relevant, and franchises like Halo and Half-Life blasted right past Quake. id’s legendary ‘90s hot streak was certainly behind it now; with every peak comes a valley. The future of id software lay on a new peak, though, and it would take over a decade to reach it. In the meantime, id’s iconic franchises had to tread water however they could. Doom got some funky little mobile games that reused their original sprites. Raven Software would have their hand at a Wolfenstein game in the meantime. What did Quake do? In true Quake fashion… mostly some weird stuff.

And Now For Something Completely Different

Remember Gray Matter’s Return to Castle Wolfenstein from 2001? I mentioned it briefly in Expansion Pack Two as part of the reason id got on the same page with John Carmack about making another Doom game. It was a fairly successful game in its day, and with success in PC gaming comes expansion packs. Splash Damage, a brand spanking new studio formed by former Quake modders, rose to the task. This new expansion was supposed to have both single-player and multiplayer content, but in an unsurprising twist from the studio comprised mostly of multiplayer modders, they were having trouble with the single-player part of that deal. In what may be the most consumer-friendly thing to ever happen in gaming, it was decided that Wolfenstein: Enemy Territory would release on May 29th, 2003 as a free, standalone multiplayer title. With player loadouts and asymmetrical objective-based matches on large maps with lots of players, it was very much in the style of Battlefield, which definitely worked considering the WWII setting. The game was added to Steam just three years ago, and it maintains a niche community. Pretty neat!

Anyways, why am I talking about this? Because the sequel to this game was a Quake game, naturally.

That’s right: the “Enemy Territory” moniker graduated from subtitle to main title with Enemy Territory: Quake Wars on September 28th, 2007. It’s the kind of decision that only makes sense from a developer’s point of view: “That Wolfenstein multiplayer spinoff we did went over pretty well, so let’s just do that for Quake, too! And it’ll be like our own little spinoff series, Enemy Territory, where all your favorite id classics become Battlefield!" By now, it’s probably beginning to dawn on you why I’ve deemed Quake’s history so “bizarre.” It began by filling in the gaps of a medieval RPG concept with FPS stuff, got a completely unrelated sequel entirely by accident, and eventually got a spinoff which was a sequel to a game from a different franchise. How many other franchises can claim even one of those feats? It’s like this whole series persists on sheer willpower.

Don’t expect this new Enemy Territory to feel much more like Quake, though. It’s another Battlefield-style shooter where two armies fight for control of huge maps, set as a prequel to Quake II that depicts the strogg invasion of Earth. There is absolutely no rocket jumping going on, you will be reloading your guns and aiming down the sights, and you won’t find any Mega Health or Quad Damage power-ups lying around. It’s a full-on military shooter whether you’re playing as the humans or the strogg. Both factions have four classes with different guns to pack into their loadout and various support capabilities, and features like vehicles and airstrikes really contribute to that all-out war feeling. In typical military shooter fashion, most guns are just variants that can all fill a set role, like assault rifle or sniper, as opposed to the no-filler classic Quake arsenal. Unsurprisingly, classic Quake guns lose their luster in this system: the railgun is just one of many snipers, and the poor lightning gun is downgraded to a mere sidearm for the strogg. Oh, yeah, the strogg get all the fancy sci-fi guns from older Quakes anyways. Pretty much everything cool is strogg exclusive, but at least you get the satisfaction of fighting the good fight if you load into a match on the human side, I guess.

This is a pretty dubious excuse for a Quake game, but it actually made for a pretty good Battlefield experience… reportedly. I have to admit I didn’t play this one; I can’t really stand Battlefield personally, so there was no way this pseudo-Battlefield game was going to be a fun time for me. It reviewed pretty well, though, and aspects such as the interesting differences between the two factions and the varied objectives of every map made it a pretty serious contender with Battlefield in the same niche. This game had some awful luck, though. Just eight days after Quake was beginning to dig itself out of the ashes, another nuclear game dropped and buried it right back under the dirt: Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare.

I’m really not the type to talk up Call of Duty. It’s like the McDonald’s of shooters these days; a series so focused on being for everyone that it fails to have any sort of identity or interesting design - and it keeps getting more expensive, too. It’s become an unimaginably lazy yearly scam that gamers, a community I become more disappointed with every day, somehow fall for every damn time. The reason Call of Duty has been able to coast on its name alone (and the general unwillingness of the average gamer to exit their comfort zone) for so long, though, is Modern Warfare. This is back before Call of Duty was a household name, back when they had to try. Its simple gameplay was complemented back then with a real single-player story and a more casual style of deathmatch that found a footing with people on both PC and console. I can’t honestly act like it was really on the same level as stuff like Half-Life 2, but that doesn’t change the fact that it was a massive phenomenon. Quake Wars’ decision to occupy a similar military shooter genre ultimately forced it into direct competition with basically the biggest shooter ever, and it most certainly did not win out. This is exactly why games shouldn’t chase trends.

With such a massive juggernaut to compete with, Quake Wars failed in pretty short order. Nowadays the game counts as abandonware, though, so you can download it for free and play with a community-made server browser even today. I may not be a fan of this game, but I always respect when fans keep something they love alive. I guess gamers aren’t always so bad. Regardless, this was not Quake’s comeback, but at least it seems like id finally learned their lesson about trying to pretend these classic boomer shooters were something they weren’t.

Dial Up Some Quake

By the late 2000s, internet browsers were getting a lot more comprehensive. We were really starting to move away from the gif-filled personal blogs with garish backgrounds to a more professional ecosystem of webpages with more advanced capabilities. Webpages were now even capable of hosting games, especially with the help of programs like the late, great Adobe Flash. I’m sure any readers around my age can remember passing free time on school computers with countless flash games from sites like miniclip and coolmathgames (whose games mostly had little to do with math, of course). Although these flash games were an important gateway into game development for a lot of people, they were always viewed in their own category compared to larger projects available on console or formal PC marketplaces. id software, however, saw browser gaming as a new market worth exploring.

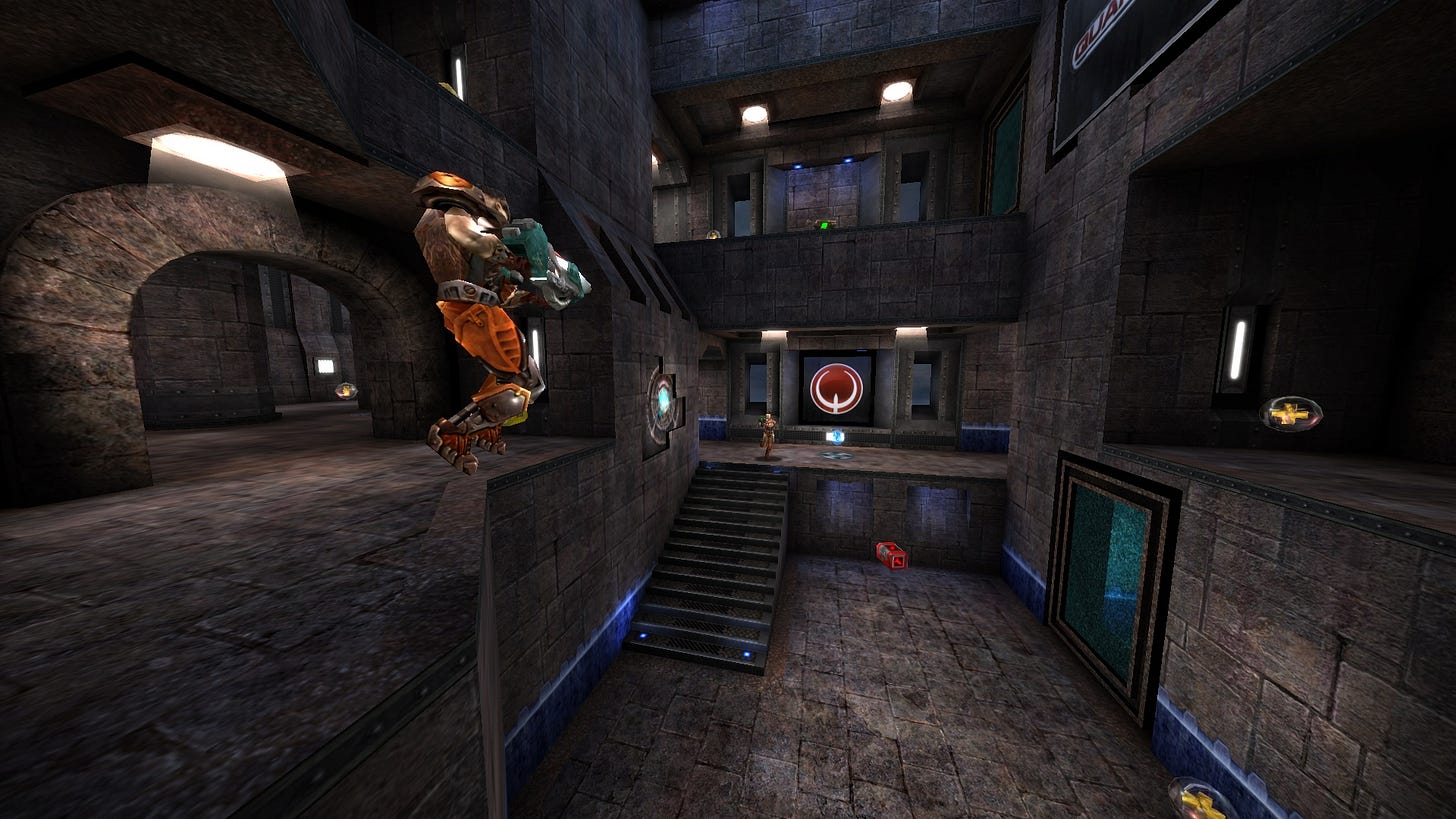

By 2008, Quake III: Arena was nine years old. It had been demanding for the hardware of its time, but tech moves fast; most decent commercial PCs could run the game by then. The appeal of most browser-based games is that anyone could boot them up through their favorite internet browsers anytime they wanted without worrying about upgrading their graphics card, and id felt that they could use Quake III to capitalize on this market of convenience. The “new” Quake Live would go into closed beta in late 2008 as a free browser-based retool of Quake III. Though it was fundamentally the same game, the addition of even more maps, modes, and quality of life changes like the ability to display your current speed made it the definitive way to play a classic title. With such convenient browser-based accessibility at everyone’s favorite price, Quake Live would not only become the new competitive standard, but inject a nice boost into Quake’s player community. I guess literally doing Quake III again can work, to an extent.

Though consumers love free stuff, companies still have costs to bear; Quake Live’s servers weren’t going to pay for themselves. The original strategy was to cover costs with in-game advertising, but not in the way you’re probably thinking of. Unlike mobile games which plaster banner ads over your screen between rounds, Quake Live’s maps would have digital billboards added to them which integrated mid-match ads directly into the game. This is almost cute compared to how ads in games work today, but it’s really no less cynical; the atmosphere of Quake’s gothic fortresses and industrial mazes would surely be interrupted when one strafe-jumps past an ad for Little Caesar’s or something. Advertisers didn’t really like it either since these types of ads were relatively easy to ignore, failing to guarantee any return on their investment.

This funding model didn’t make it to release, although the vestigial billboards remain in many maps with basic Quake Live logos covering them forever. Once the game left beta for its formal launch on August 6th, 2010, the game instead had subscription tiers for additional features. Premium subscribers could access a number of additional maps and modes and start their own in-game clans, while Pro subscribers could host their own servers and invite Standard players to play on Premium server content. Premium was only $1.99 per month and Pro just $3.99 a month, so even though the features were basic, the costs matched. Much of the game was still completely accessible for free, and the fact that Pro members could effectively share some of their benefits kept the game relatively consumer friendly. It’s not like today, where mountains of cosmetic items hide behind paywalls which could get you entire games… sigh.

By 2013, browser-based gaming had failed to grow into some kind of major market and many browsers were beginning to phase out support for gaming plugins. Quake Live was affected, migrating to its own client with a similar business model. On August 27th, 2014, the game had an update intended to grow the audience. Strafe-jumping and other jump-based movement techniques were made easier by a convenience feature allowing players to hold down spacebar instead of timing presses to repeatedly jump. Certain game modes had loadouts added, allowing players to start with their favorite weapons as Call of Duty and other popular shooters of the day allowed. Loadouts don’t really work in Quake, though, because the game is designed around more powerful weapons being map objectives to seek out. If everyone can spawn in with a rocket launcher in their hands, things get chaotic pretty quick. There was also a new heavy machine gun weapon added, not that it actually dethrones the lightning gun or anything. Come 2015, the game eventually just hopped onto Steam and dropped its subscription model in favor of a $10 price tag for unlimited access to everything.

So, did Quake Live bring Quake back? Not really, but it didn’t exactly need to, either. It became a central hub for all things Quake, bringing the most refined gameplay in the series to the widest audience possible with more content and improvements than ever. It’s the sort of game fans of any franchise deserve, and the one they usually end up having to make themselves like with Quake Wars’ fan patches or Titanfall 2’s Northstar server client. It’s still stuck in what Quake once was, of course - it’s literally still Quake III: Arena - but what Quake was is pretty cool, and it’s unequivocally good for access to that experience to be maintained like this even if it’s the only online game I’ve played that still asks me to set up port forwarding on my router. Fortunately, though, id had finally stumbled through its awkward age and come out on the other side. Soon, they would bring a revolution upon the world of boomer shooters. What was old would be new again, and Quake would once again have a chance to take back its crown.

Could Quake rise again in a world which was welcoming boomer shooters once again? Find out in “Episode Seven: Championship Bout,” out now!